خشک سیمی خشک چوبی خشک پوست

از کجـــا می آیـــــد ایــن آوای دوســـت؟

Khoshk seemé, khoshk chobé, khoshk post,

Az koja me aayad een aawaay Dost?

(Dry string, dry wood, dry hide,

Whence cometh these succulent tones of the Friend?)

The Afghan rubab

By Professor John Baily September 2016

This is the national instrument of Afghanistan. It is regarded with great respect for its sound and for its spiritual connotations. The rubab is a short-necked double-chambered plucked lute with three main strings (tuned in 4ths), four frets (giving 12 semitones to the octave), two or three long drone strings, and up to fifteen sympathetic strings. It is the sympathetic strings that give the rubab its special sound. They are tuned to the notes of the rag (‘melodic mode’) being deployed, and reinforce the sound of each note as it is played. The shortest sympathetic string is raised by a protuberance on the bridge so it can be easily struck in isolation and used as a high drone in complex rhythmic patterns that are the hallmark of the virtuoso player. The lower chamber has a skin belly, while the upper has a wooden lid that serves as the fingerboard. This is often highly decorated with intricate mother-of-pearl inlays.

The Origins

The origins of the Afghan rubab are unclear. It is a member of an ancient family of double-chambered lutes that includes the Indian rubab, the Iranian tar, the Tibetan danyen, the Pamir rubab, the Dulan rubab, and the Kashgar rewap. Its most distinctive features are its singular shape and in having sympathetic strings. With minor differences the Afghan type of rubab is also found in adjacent areas of Pakistan and Iran, and in Kashmir. In the nineteenth century it was common amongst the Afghans settled in the Rokhilkand area of North India, especially around the city of Rampur, who traditionally served as mercenaries in the Mughal armies and were much involved in the supply of horses from Central Asia to India for military purposes. In the mid-nineteenth century it became transformed into the Indian sarod, either in Lucknow or in Calcutta.

“The layout of notes on the fingerboard of the rubab makes it easy to play the three main melodic modes of Pashtun music: Bairami, Kesturi and Pari.”

EMBODIMENT

The rubab has a special connection with the Pashto speaking population of Afghanistan and embodies certain features of Pashtun music. Its special acoustical properties are suitable for a fast percussive style of playing, with emphasis on permutations of right hand stroke patterns and dramatic rhythmic cadences. The layout of notes on the fingerboard of the rubab makes it easy to play the three main melodic modes of Pashtun music: Bairami, Kesturi and Pari. The rubab is thus the ‘ideal’ Pashtun instrument.

It is also widely used for playing the art music of Kabul, where the rubab is the principal instrument for the accompaniment of ghazal singing. The texts of these ghazals are very often of a Sufi spiritual nature, by poets such as Hafez, Bedil and others. TheAfghan rubab is also used for playing two genres of instrumental art music. One is the naghma-ye chahartuk, ’the four part instrumental piece’, often used as a group instrumental at the start of a concert of music, intended to warm up the instruments, the musicians, and the audience. The other genre is the naghma-ye klasik, ‘the classical instrumental piece’, the Afghan equivalent of Indian alap and gat, which allows ample scope for melodic improvisation. Many of the rags of North Indian music are known in Afghanistan, sometimes under rather different names (Bhairavi become Bairami, Bhairav become Beiru), and with different melodic characteristics.

Some leading rubab players

Ustad Mohammad Omar

Afghanistan's foremost player of the rubab. Although he received a basic training in playing the rubab, Mohammad Omar aspired to be a singer, and trained in ghazal and rag singing. Due to illness he was forced to give up singing and specialise in playing the rubab, at which he came to excel. In 1949 he was given the official title of Ustad. He became the principal rubab player at Radio Afghanistan, the leader of various ensembles, the composer of many instrumental sections (naghma) for popular songs, and of many light instrumental pieces for small radio ensemble. He became one of the best known and highly esteemed of Afghan musicians. In 1974 he spent 3 months at the University of Washington as artist in residence.

Ustad Rahim Khushnawaz

From Herat, a son of Amir Jan Khushnawaz, who was in turn the student of Ustad Nabi Gol. Through this connection Ustad Rahim became very familiar with the art music of Kabul and was especially noted for his brilliant ghazal accompaniment. He was also famous for his interpretations of Herati folk melodies, adding extra frets to the rubab to enable it to play the microtones typical of the local style.

Ustad Ghulam Hussain

From Kabul, one of the principal students of Ustad Mohammad Omar. Taught rubab at the Aga Khan Music School in Kabul for ten years and has made numerous visits to Europe for concert tours.

Ghulam Mohammad Attaie

From Herat, originally an amateur musician, a motor mechanic by profession. He studied extensively with Ustad Mohammad Omar and developed a style very much like that of his teacher. Lived and worked as a professional musician for some years in Europe before his untimely death. He was also a gifted maker of rubabs.

HomayOun Sakhi

From Kabul, his father Ghulam Sakhi was a brother-in-law of Ustad Mohammad Omar, and through this connection Homayoun received a thorough grounding in the art of Rubab playing. He honed his skills while in exile in Peshawar with other musicians from Kabul and is recognised today as the leading exponent in the field of Rubab playing and a well-known figure in the international world music scene. He currently resides in California.

Ustad Essa Qassemi

He was a grandson of the famous Ustad Qassem, King Amanullah’s Court Singer in Kabul in the 1920s. Essa Qassemi lived for many years in Kandahar and his distinctive rubab style incorporates elements of Hindustani vocal music, for as well as playing rubab he was something of a classical singer. Through his recordings we gain some insight into the little-known but distinctive style of rubab playing in Kandahar.

Ghulam Jailani Nabizada

One of five musician sons of the celebrated Ustad Nabi Gol, originally from the Tirah frontier region, later settled in Kabul. His father was a leading vocalist and multi-instrumentalist who introduced the classical music of Kabul to Herat in the 1930s. Ghulam Jailani developed a more sarod-like approach to rubab playing, rather closer to Indian music than the playing of Ustad Mohammad Omar, with very free and imaginative melodic improvisations.

Much more information about the rubab can be found on the Online Afghan Rubab Tutor www.oart.eu. See also War, Exile and the Music of Afghanistan. The Ethnographer’s Tale, by John Baily (paperback, Routledge, 2016).

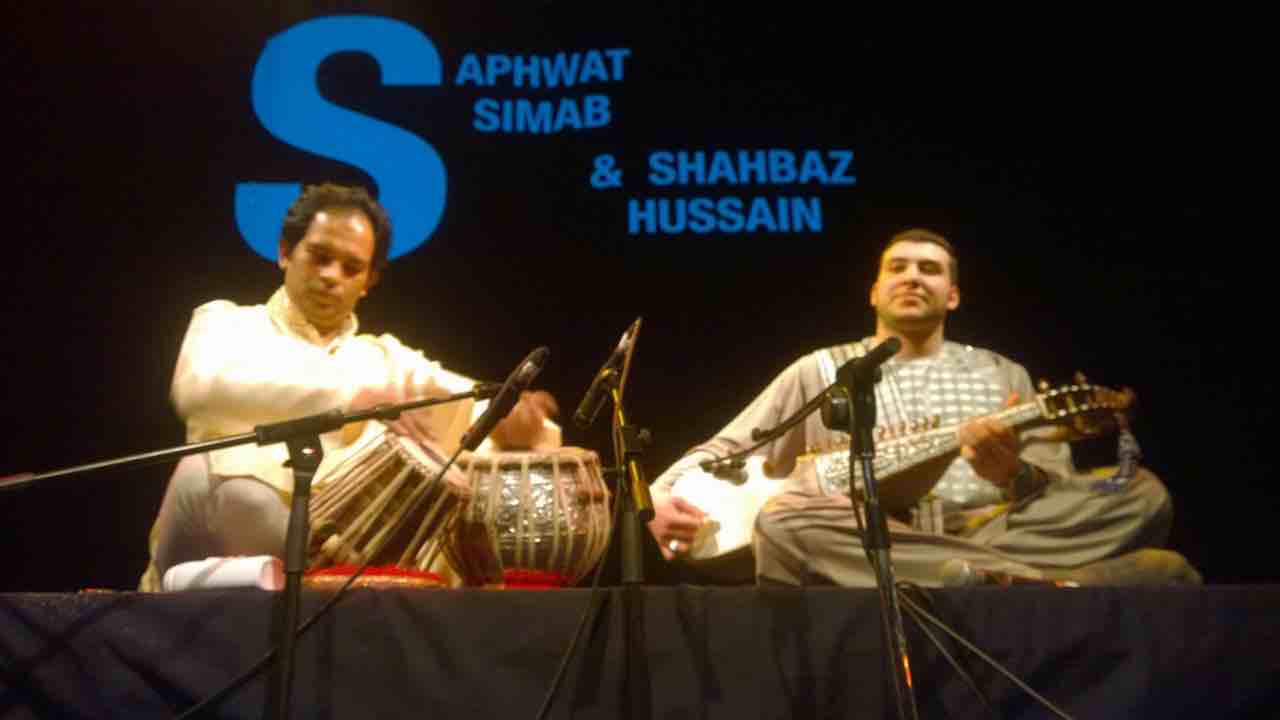

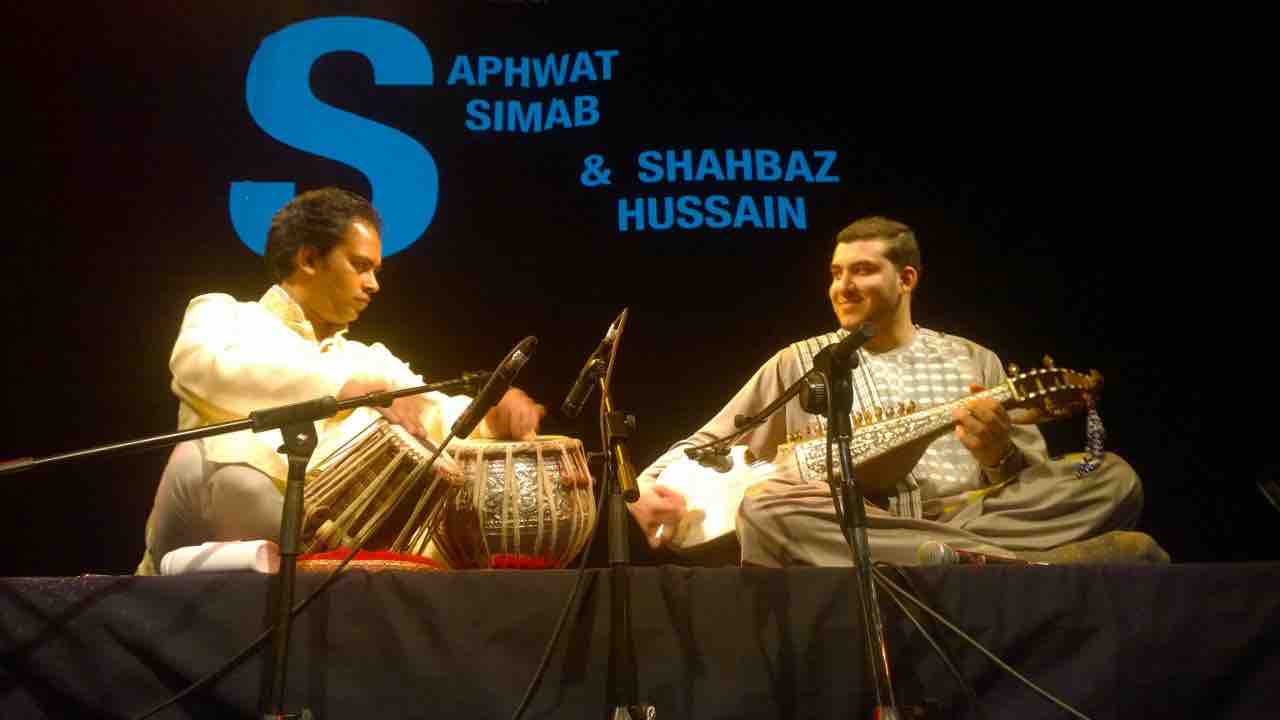

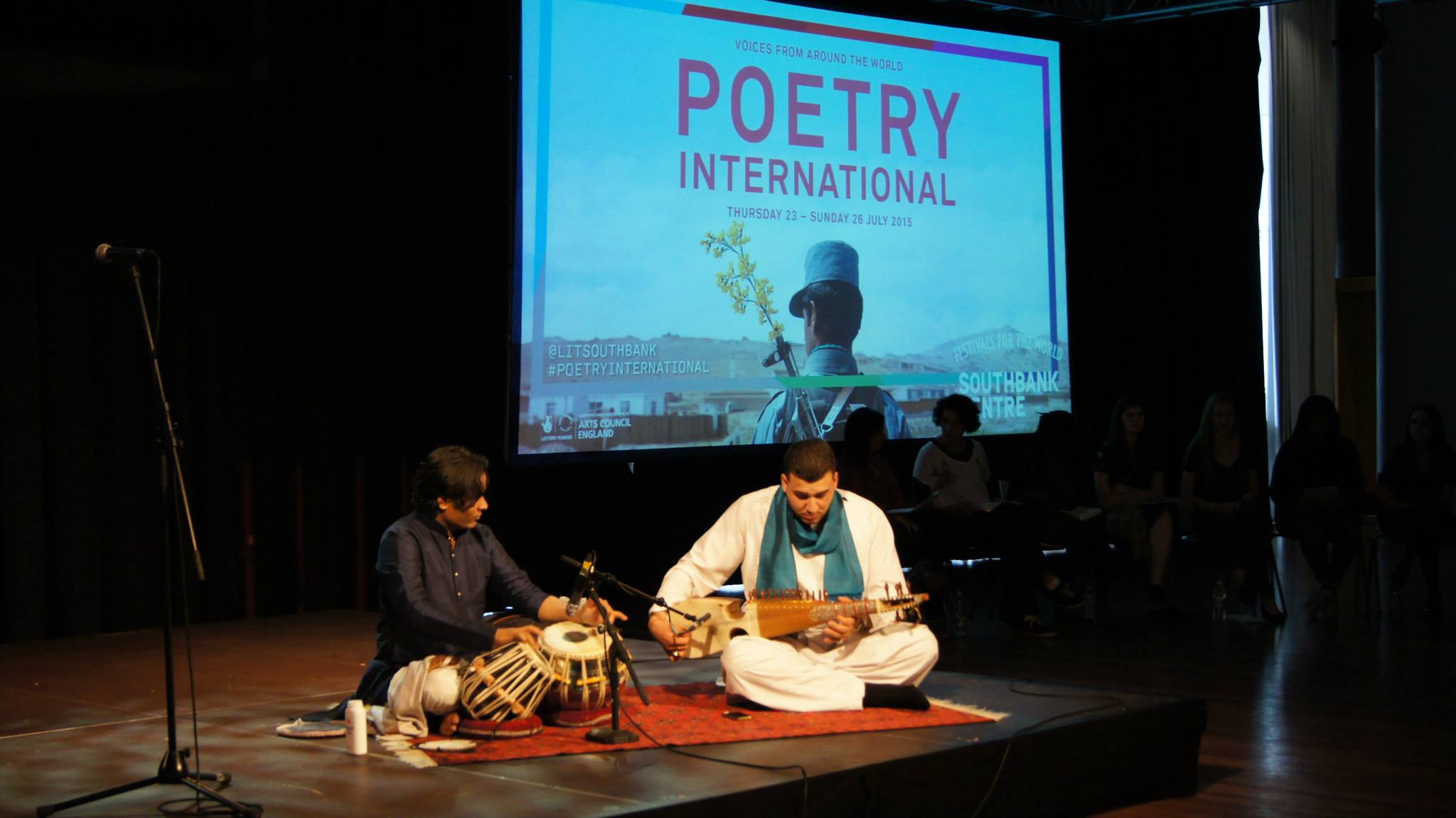

Saphwat Simab

Saphwat Simab

Saphwat Simab

Saphwat Simab

"THE POLISHING OF A GEM"

Some are born talented, they say, others are born lucky. It may be that Saphwat Simab was born both. Son of the founder and owner of The Music Room @ Friend’s Hearth, Saphwat, as any father of a young boy can testify, loved to touch and handle his father’s things, among them an Afghan rubab on which Rahmat attempted to play some tunes every now and then. Until then, Saphwat had given no inkling of any special talent except in mischief, so it was with amazed surprise that one day Rahmat caught his 13 year old son (whom he had expressly told not to touch his rubab), playing a wonderful tune, all on his own, without being taught a thing, on the instrument. Since that day, Saphwat hasn’t looked back in his breath-taking trajectory towards mastery of the quintessential Afghan musical instrument. Initially with nothing but his talent and his father’s encouragement to drive him forward, Saphwat showed an extraordinary aptitude and ear for picking up complex tunes. But he was not only talented, he was also immensely lucky in that he had the founder and owner of TMR for a father. Immersed in the music-reverberating atmosphere of The Music Room @ Friend’s Hearth and inspired by the spellbinding performance of music ustads and pandits performing there, he was soon playing intricate ragas. But talent without nurture is an unpolished gem, so, at 17 years of age in 2015, he officially became the pupil, through a ghanda bandhan (gur maany) ceremony at TMR, of perhaps the foremost rubab maestro in the world, Ustad Homayoun Sakhi. And, with The Music Room @ Friend’s Hearth as his nursery and playground, everyone expects Saphwat’s artistic talent and output to reach for the stars. He still has a long way to go, but these clips are snapshots of his career towards the heights he is expected to conquer...